Europe’s Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II) is the result of a long and intense legislative procedure and while it is considered far from a perfect plan, the EU thinks it is the best they have to bring decarbonization to the EU transport sector.

In RED II, which was adopted in December 2018, the overall EU target for renewable energy sources consumption by 2030 has been raised to 32%. The Commission’s original proposal did not include a transport sub-target, which was introduced into the final agreement and now member states must require fuel suppliers to supply a minimum of 14% of the energy consumed in road and rail transport by 2030 as renewable energy.

This casts into the question the petroleum industry’s fossil fuel market share in the EU transport sector and poses the question of how to best manage a steady decline as the EU long-term trajectory is to move towards zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

In order to support this transition, RED II increases the overall blending requirement on fuel distributors for all segments of transport and tries to promote advanced biofuels. Written in the legislation, consumption must shift away from crop-based and waste-based biofuels and be aligned by 2030 with the following objectives:

- crop-based biofuels must account for less than 7% of the total diesel output

- waste-based biofuels must account for less than 1.8% of the total diesel output

- advanced biofuels output must exceed 1.8% of the total diesel output

According to RED II mandates, the EU biodiesel demand for road transport is expected to grow by about 10-14% in the period from 2021-2030.

EU crop-based biodiesel demand is expected to start declining from 2024 because of feedstock caps on blending rate constrained by RED II mandates.

Additionally, waste-based biodiesel demand consisting mainly of used cooking oil (UCO) and waste animal fats will reach the RED II maximum levels by 2026, followed by a steady decline onwards. An issue with feedstock supply for waste-based biodiesel is that Europe must today import almost half of its waste-based feedstock needs and the availability of waste-based feedstock is limited.

Even more of an issue are the advanced feedstocks -whose supply is almost zero percent today. The minimum share required by RED II will produce a huge strain on supply as demand surges. Demand in the EU for advanced feedstocks are expected to reach over 3.5m metric tons by 2030. This projected surge in demand creates major uncertainties around global advanced-feedstock availability as there are limited available public information and studies on the topic.

A few of the feedstocks considered advanced and of interest to our industries are crude glycerine, tall oil pitch, tall oil, lignin, black liquor and palm fatty acid distillate (PFAD).

Renewable Diesel Expansion Poised to Surge

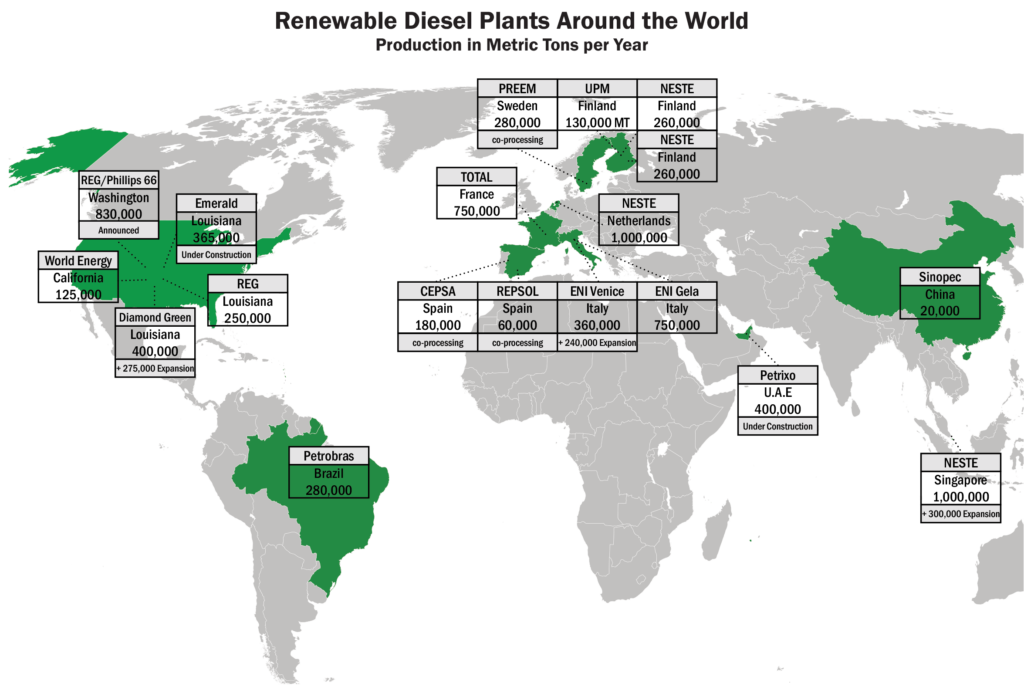

Surging renewable diesel demand is expected worldwide and renewable diesel capacity is expected to triple globally by 2025.

Renewable diesel, also known as HVO, is a liquid fuel produced by hydrotreating catalysis of triglyceride-based biomass such as vegetable oils, waste cooking oils or animal fats. Renewable diesel qualifies as a drop-in fuel characterized by the same chemical structure as conventional diesel fuel. It can be blended with conventional diesel fuel, can use the same fuel supply infrastructure and does not require adaptation of the vehicle powertrain or engines.

In the past few years, hydrotreating of vegetable oils, animal fats or waste cooking oils has been proposed as an alternative process to trans-esterification for producing biofuels. This process is considered to be an alternative way to produce high-quality bio-based diesel fuels without compromising fuel logistics and engines.

Renewable diesel plants can use a wide range of feedstocks, such as native vegetable oil, animal fats, fish oil and used cooking oil, as well as oils that are byproducts of different industrial processes, such as tall oil from the wood and paper industries, palm oil mill effluent and PFAD.

Production of renewable diesel in Europe has picked up since 2012. Petroleum companies, such as Neste, Eni and Total have been the main groups promoting the increased capacities.

Output in the EU was estimated at about 2.8bn liters (740 million gallons) in 2018 and expected to rise a little to 3bn liters in 2019. While planned production facilities in France and Italy are expected to boost production to 3.5 and 4.5bn liters respectively from 2020 onwards.

As new capacity comes online supply of preferred feedstocks available is expected to be less than the demand. It is important to discuss the legislated phaseout of some key feedstocks that could provide the volumes necessary for the increased capacity projected to come online.

Last year, when the EU extended the RED II with a new 2030 target for biofuels and other renewable energy in transport last year, it included language capping and phasing out the contribution of high indirect land-use change (ILUC) risk biofuels towards that target. The RED II spelled out an exception for low ILUC risk biofuels that avoid impacts on agricultural commodity markets by producing feedstock on unused land or from yield increases.

In February 2019, the European Commission categorized palm oil as a high ILUC biofuel crop. Palm oil was the only biofuel feedstock crop to be classified as high ILUC, meaning that it cannot be counted towards EU green targets and that it will be gradually phased out by 2030.

The rule has long-term effects for the feedstock matrix, but also sparked controversy earlier this year as Total was set to start up its La Mede biodiesel refinery. The refinery’s use of palm oil sparked opposition from farmers producing vegetable oil and from environmental activists. Farmers expressed concern about palm oil competing with locally produced vegetable oil and environmental activists cited the deforestation caused in producing it.

To assuage the objections Total committed to use less than 300,000 metric tons of crude palm oil per year at La Mede out of a total of 650,000 metric tons, with the rest coming from oils from other plants, recycled animal fat, cooking oil and industrial oil.

France’s National Assembly adopted an amendment in mid-November 2019 delaying until 2026 the end of palm oil’s tax advantages, a parliamentary document showed on Thursday, a move that could benefit French oil major Total.

Just over 51%, or 3.9 million metric tons, of crude palm oil imported into the EU in 2017, largely from Malaysia and Indonesia, was processed into biodiesel, according to the European vegetable oil and protein meal industry federation (FEDIOL) in Brussels. Palm oil makes up about a third of the content of biodiesel in the EU, with the rest from rapeseed oil, soybean oil, and sunflower oil.

While palm oil faces phaseout under the high ILUC designation, soybeans could take their place as a feedstock for EU biofuel. The EU forecasts that soybean imports from the US will increase from 39%–or 2,439 metric tons in marketing year 2017-2018–to 75%, or 5,182 metric tons, in 2018-2019.

The European Commission has started a process to recognize US soybeans as a sustainable feedstock for EU biofuels. In December 2018, it published a draft decision acknowledging that the US Soybean Sustainability Assurance Protocol met EU biofuels sustainability criteria.

In February we will delve deeper into the feedstock supply scenario for the advanced biofuels category and how it could affect the pine chemicals industry.